May 14, 2025

AUTHOR Nick Stone

Early Architecture of UK AI Policy and the ChatGPT Inflection Point

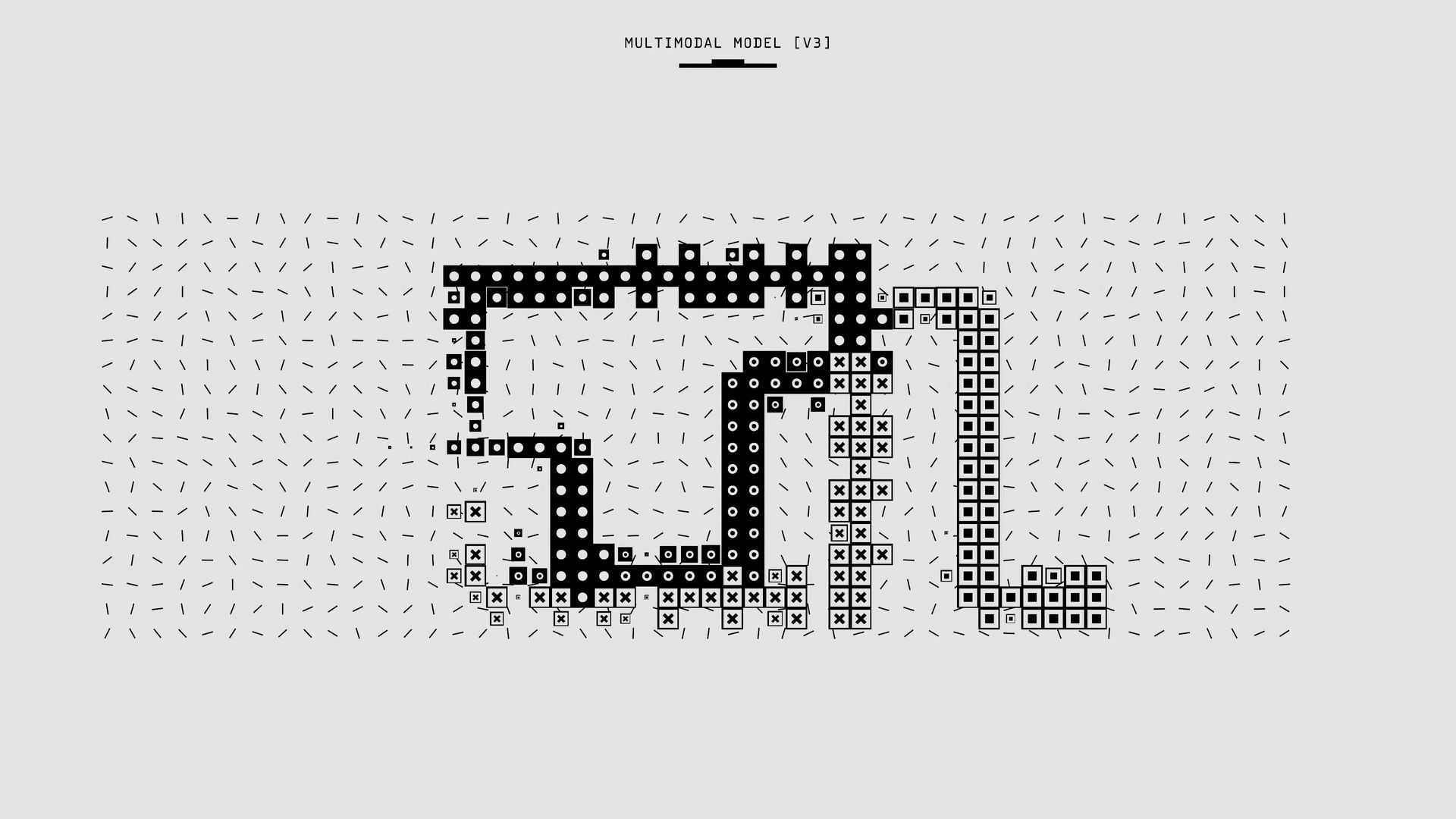

In 2017, then–Prime Minister Theresa May commissioned Professor Dame Wendy Hall and Jérôme Pesenti to produce a landmark report on artificial intelligence (AI), technology, and employment. The resulting UK AI strategy launched that October, creating the AI Office and the independent AI Council. While the Office was staffed by civil servants to oversee implementation, the Council was an expert advisory body.

The Hall–Pesenti report made 20 recommendations across five domains, with an emphasis on data usage, storage, and access. It also addressed AI skills development, leadership, and how businesses could adopt AI tools. A notable recommendation was to position the Alan Turing Institute as the UK’s national AI hub. The government endorsed the strategy, allocating £1 billion in public funding as part of its broader industrial strategy. However, the Turing Institute’s role evolved differently than anticipated, partly due to overlap and competition with university-led research initiatives.

In November 2022, OpenAI’s public release of ChatGPT marked a profound shift. Suddenly, large language models were no longer theoretical or confined to enterprise use—they were widely accessible and immediately impactful. In the aftermath, prominent tech executives lobbied UK policymakers, framing AI as an existential risk. This influenced a shift in policy tone—from one of opportunity to one focused on risk management. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak responded by establishing the AI Safety Institute and, notably, disbanding the AI Council—although the rationale for this decision remains opaque.

AI and the UK’s Global Economic Positioning

The current UK government views AI not only as a technological imperative but also as an economic strategy. Its objectives are threefold: enhance infrastructure (particularly data centres), expand domestic AI expertise, and accelerate AI adoption across industry. The UK seeks to become a global AI hub, while avoiding a “superstar” economic model that is vulnerable to foreign acquisition.

However, policy formation is complicated by uncertainty around which AI firms and technologies will endure. The UK may be better served by fostering a diverse AI ecosystem, rather than replicating dominant US platforms such as Google.

Comparable efforts are underway elsewhere. The French government, for example, has supported national champion Mistral and invested in foundational models—highlighting the risk that governments may back firms that ultimately underperform.

Legal and Practical Considerations

Central to AI infrastructure is the expansion of data centre capacity. However, UK law—particularly in relation to copyright and data processing—applies only to centres located on UK soil. This has implications for AI model training, which increasingly relies on vast and varied data inputs. Moreover, data centres are highly energy-intensive; a typical US facility consumes around 200 megawatts—enough to power approximately 200,000 UK homes or 10 NHS hospitals annually.

The UK government also aims to close the AI skills gap. Upskilling initiatives are underway, with recognition that the skillsets required to build physical infrastructure differ from those needed to design AI models. The UK benefits from a strong talent base in healthcare and education, with labour costs roughly half those in the US Vocational training, including hands-on data centre work, is being promoted, alongside efforts to support local government in AI adoption and retain academic talent.

Barriers and Legal Risks

Funding remains a significant constraint. Public finances are tight, and the government is relying heavily on private investment. This raises sovereignty and governance concerns: private sector involvement in AI infrastructure and model development could outpace regulatory capacity.

Copyright is another major challenge. Legal disputes over the use of protected works in model training are ongoing. Some propose opt-out mechanisms for authors and rights holders, but questions around enforcement and transparency persist.

From a regulatory standpoint, the UK has so far chosen not to introduce dedicated AI legislation, relying instead on existing legal frameworks. This may prove insufficient as vertically integrated tech firms gain market power—especially those controlling data and cloud infrastructure. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority is already examining the cloud computing sector.

Additionally, the UK must remain alert to US developments. A second Trump administration could take a significantly different approach to AI regulation, with implications for transatlantic legal alignment and data governance.

A Legal-Strategic Outlook

The UK has a credible opportunity to become a global AI hub, provided it avoids over-centralisation or imitation. A strategic, legally grounded approach—balancing innovation, regulation, and sovereignty—will be critical. For UK and US lawyers, understanding these evolving dynamics is essential as AI regulation, intellectual property, and cross-border data governance become defining issues in legal practice.